I

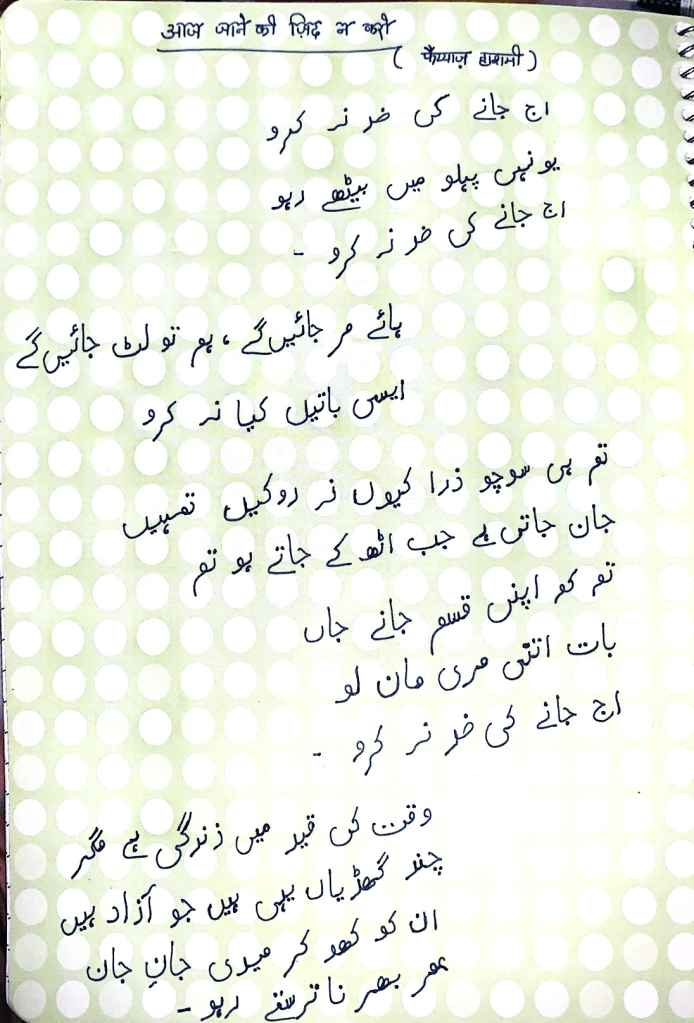

आज जाने की ज़िद न करो

यूँ ही पहलू में बैठे रहो

हाय, मर जायेंगे

हम तो लुट जायेंगे

ऐसी बातें किया न करो

तुम ही सोचो ज़रा, क्यों न रोकें तुम्हें?

जान जाती है जब उठ के जाते हो तुम

तुमको अपनी क़सम जान-ए-जाँ

बात इतनी मेरी मान लो

आज जाने की ज़िद न करो

वक़्त की क़ैद में ज़िंदगी है मगर

चंद घड़ियाँ यही हैं जो आज़ाद हैं

इनको खोकर कहीं, जान-ए-जाँ

उम्र भर न तरसते रहो

आज जाने की ज़िद न करो

कितना मासूम रंगीन है ये समाँ

हुस्न और इश्क़ की आज मेराज(मिलन) है

कल की किसको खबर जान-ए-जाँ

रोक लो आज की रात को

आज जाने की ज़िद न करो

-फ़य्याज़ हाशमी

Like many, I discovered Farida Khanum too, after encountering, her ceremonious rendition of ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’.

Interestingly, many in their enchanted ignorance, regard it as a ghazal, more often than not. Pran Nevile, sharing an incident at Begum Akhtar’s memorial concert organised at the India Habitat Centre. The performing artist on being requested to sing this popular number responded to the audience, through the organizers that, she would sing it only if anyone would name the writer of the ”famous” ghazal{?}. ‘Interestingly, no one in the audience of over three hundred gave the correct answer’.

The writer was Fayyaz Hashmi, a prolific lyricist who had penned over 500 songs before moving to Pakistan in 1947.

Composed by Sohail Rana, it was initially sung by Habib Wali Mohammad, for the film Badal aur Bijli, 1973.

It was, however, in the 1980s, when Farida Khanum recorded its slow rendition, for PTV and subsequently live public concerts, it went on to be regarded as the ‘most iconic ode to love and longing‘, with its enchanting melody and poignant lyrics, in the entire subcontinent.

She in her inimitable style, infused her versatility into the song, making it enchanting, appealing and endearing each time and version, she performed it, across shows and recordings. In 2015, this song was recomposed by Strings for Coke Studio(Season 8, Episode 7), sung by Khanum herself.

In the words of the writer himself, on being praised for writing this piece, Fayyaz Hashmi had once said, “No, I don’t think I could make it, whatever Allah taala made me write, I could put down only so much on the paper.”

He further added, ‘But, just to clarify you here, not just Pakistan but even Hindustan has a huge contribution for this nazm, especially my bygone days of childhood, in my dear city Kalkatta.”

II

Farida Khanum- the enchanting vocalist & the ghazal singer:

On being asked about how she came to sing the timeless Aaj jaane… she replied, “I think, it was something that had to reach you (the people) and I was there to sing it. I sang it for a film that disappeared from the theatres within three days of its release. Later, when I sang it at a private function, the audience appreciated it, word spread and it became popular.”

The success of the song didn’t propel her towards the world of cinema, although she did sing for a number of Pakistani films and has also acted in a few.

In an excellent analysis of this rendition, Ali Sethi in The Djinn of Aiman, 2014, traces a trail or path, with the song set in Aiman Kalyan, the evening raag associated with love. Describing this superlative of the musical finesse, he writes that “her wilful, uneven pacing of the lyrics creates the illusion of a chase, a constant fleeing of the words from the entrapments of beat,” thus creating “a bewitchingly layered song, one with a cajoling, comforting, almost foetal ebb and flow to it, but also with the plunges, scrapes, and gasps of a ravenous consummation. It has bliss, strife, love, sex.”

It is, however, her ‘trademark style‘, reflecting her classical training under Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan of the Patiala gharana, (a technique, where strategic lags and compressions in the singing can enhance the pleasures of a deferred rhyme.)

For ‘the song that was ‘fast’, she made it ‘slow’; the song that was ‘light’, she gave it ‘soz’ (pain); the original that was sung in the ‘filmi style’, she decided to sing it in a ‘somewhat altered style’.’

Khanum, he says, ”leans on the raag repeatedly for results: her ‘yunhi pehlu mein baithay raho’ is so persuasive because she is literally holding the note, in this case the Gandhar or Ga of the raag, which happens to be its vaadi, or dominant, sur. Then there is the song’s beat-cycle—here the Deepchandi taal of fourteen matras.”

Renouned for her ‘áarha’ style, Khanum manages to layer it with an ‘additional tension‘, between the tabla and her voice, occasionally converging at the samm/first bol of the cycle.

”But what after these outlines have been described? How to account for the slightly torn texture, the husky tone, the maddening rass of the voice?”

Also, her brilliant rendering of the word ‘haye’ in the phrase ‘haye marr jayein gey’?

Rekha Bhardwaj, once is said to exclaim, ‘Yeh gaana hai hee “haye” pey.’ (This song is all about the ‘haye’.)

Infact in the original version the word ‘haye’ is used as an exclamation, but when Khanum sings it, it is tweaked to a ‘dizzying upward glide’, ‘a veritable swoon’, making it ‘thematic locus, of the lyric’.

An interesting reference is cited when in order to understand, if such a phenomena be broken down, Sethi asked Farida Khanum to show the note-by-note progression of her ‘haye’ on the harmonium. This, instead, she could mysteriously produce using with her voice. She ”would close her eyes, put on a smile, tilt her head, throw a hand in the air and let the ‘haye’ out.”

To, then compress her musical and cultural evolution, across the transitional decades of 1930’s to 1980’s, is both ‘cathartic and extra-musical’. Her role as a transmitter of djinns is magnified by social and historical contexts.

Sethi adds, further in this regard, ”when she sings ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’, she is passing on the cumulus of centuries—the laws of Aiman, according to one legend, were laid down by Amir Khusro in the thirteenth century—in an ‘accessible, contemporary, but fundamentally uncompromised form‘.

In ways more than many, it is remarkable, to think how ”this process is made poignant and ironic by our ignorance: how many of the amateurs who upload videos of themselves singing ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’ on YouTube and Facebook know what they are really channelling?”

So while ‘the enduring appeal of a singer like Khanum is nostalgic, yes. But it is also heightened by our condition, which is one of rootlessness and over mediation, and by our corresponding thirst for what is true, rare, original, and sublime.’

Also, listen to this –

III

For Khanum, as Sethi wonders, if she even had a faint idea as to how popular she remains among the young people, the YouTube listeners.

‘Oho,’ she said, affecting curiosity.

Citing an interesting dialogue, between him and Khanum, as he showed one of her video on YouTube, ‘‘Ai kee ay?’ (What is this?), pointing to the video links on the screen.

Khanum peered at the screen, answering – ‘Ai te mein aan,’ (That’s me.)

On playing one of the several ‘çovers’ of ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’, and subsequently, reading out a few of the comments, on her version of the song, comes the response,

‘Soulful!’; ‘What a beautiful voice!’; ‘133 dislikes—for what??’; and ‘My all-time favourite ghazal.’

‘Ae hunay hee aya ai?’ (Did this one come just now?) Khanum asked, tentatively pressing a finger to the screen.

The response to which was how these comments had been accumulating for years, and would continue to gather for as long as people listened to her song.

‘Mein hairat mein hun,’ (I am amazed.) Adding further, she exclaimed- ‘Ai magic horyaai, magic.’ (This is magic, this is magic.)”}’

Indeed, it is!

IV

About Farida Khanum:

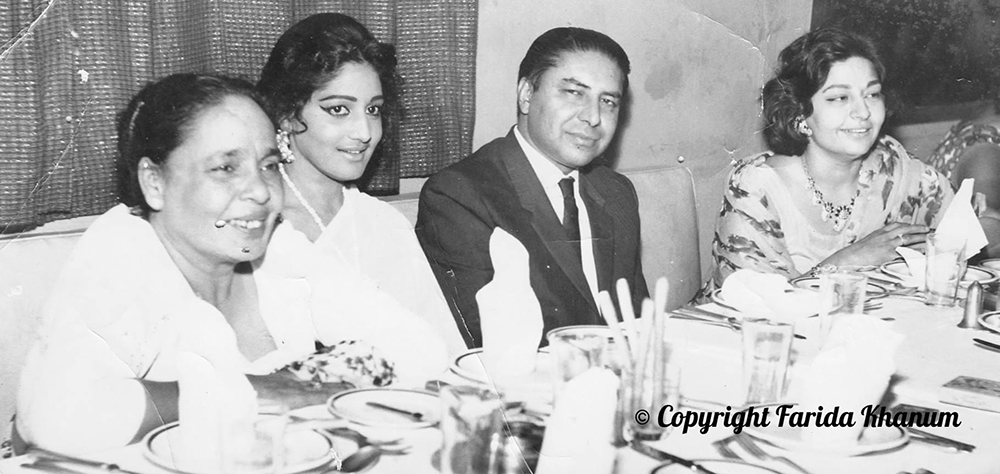

Born in Amritsar, Khanum spent the formative phase of her life in Calcutta where her sister, Mukhtar Begum was a leading stage actress and singer. Here she was exposed to the music of Akhtari Bai and to the presence of other stage performers like Ratan Bai, Taani, Durga Khote, Kajjan, and Naseem Bano.

She was a shagird of Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan, the son of Ustad Fateh Ali Khan, who taught to render the very complicated taans. She recalls, how her riyaaz would last up to 4 hours a day, perfecting the modulations, pitch, notations and breathing while she was being trained. She also admitted however, that, in thumri and ghazal singing, she was more influenced by Ustad Barkat Ali Khan.

In 1947, the family migrated to Pakistan, making it difficult for Khanum to continue her training as she would have liked. This led her to lament for she could match the likes of artists like Roshan Ara Begum or Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan ‘who could sing for three hours without a break, before a rapt audience’. In her own words, “I thought what’s my mukaam (stature) in front of them? I then decided to stick to light classical music. Understanding my weaknesses helped me to build on my strengths. I had always been interested in poetry and that is when I thought I should shift to a semi-classical genre, rather than struggle in a difficult field.’‘

‘I used to get 50 (Pakistani) rupees per show and that was quite a lot those days,’ laughed Khanum.

Some of her early ghazals in 1950s were Muddat hui hai yaar ko mehman kiye hue in Raag Anandi and Raha yoon hi na mukammal ghame isq ka fasana in Raag Aiman.

Khanum, herself, considered three cities — Calcutta, Amritsar and Lahore – very significant in her life. “Though I am from a pure Punjabi family of Amritsar, but owing to my ustad, I learnt to speak excellent Urdu that helped me sing ghazals where accent matters a lot.”

She recalls, ”All that I know today is because of my training in Amritsar. I learned many Hindustani ragas in the style of the Patiala Gharana, which is known for its graceful execution of thumris and khayals. I could have been a classical singer if I had not migrated.”

Khanum’s recitals epitomise chaindari (a leisurely style of singing) and nafasat (the sensitive enunciation of lyrics), two essential ingredients for a good ghazal performance.

Her first concert appearance was in Lahore in 1950 in which renowned singers like Zeenat Begum and Iqbal Begum presented their ghazals too.

She has no qualms admitting that she barely got time for riyaaz while bringing up her children. She explains, “Even if I wanted to do riyaaz, there was so much post Partition opposition to music in Pakistan that if one sang in the morning, the neighbours would complain.”

In 2005, she was awarded the Hilal-e-Imtiaz, Pakistan’s highest civilian honour, the only other Pakistani artist accorded this honour being Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. She was also honoured with the prestigious Indian distinction, the Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan award(named after Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s father) in 2005.

The tribute, ‘If the entire world of ghazal music is to crown a single soul, then it has to be Farida Khanum, the celebrated ghazal queen of Pakistan’. Referring to her, the then Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh had said, “Listening to your music we feel the power and presence of God.”

V

Her times, Her peers:

There is, to be sure, an element of truncation in Khanum’s musical trajectory: she has said many times that Partition, which resulted in the loss of her Amritsar home, signaled the end of her training and forced her to make compromises—personal as well as musical.

Sethi added further in this regard as to how, ”for a few years, while living in the alien hill-bound city of Rawalpindi, Khanum shuttled regularly to Lahore to sing for radio and act in films, failing to make an impact. Soon she surrendered to marriage, and gave up singing at the insistence of the industrialist who offered her the securities of a ‘settled life’. Later, when she returned to music, she took up not khayal or thumri but the accessible and mercifully ‘semi-classical’ Urdu ghazal.”

Added to this was two conjoined aspects, of her early musical training by her Ustad, who rather emphasized ‘íngenuity and dynamism over fidelity to rules’ and her exposure and influence, of the charm of Begum Akhtar, who was a friend of her sister’s and a regular visitor to their house in Calcutta. The latter likewise, was not bound by obligations of form and lineage, and valued presentation, and quirks more than mere laws and structures of raags and taals, making it distinct in crucial ways. So while some of her peers raced towards a climax, to display their grasp over the taal, Khanum rendered interesting forms of anti-climax;

Undisputedly, then, in this way, she was a born performer.

Incidentally, both, Begum Akhtar and Farida Khanum, had the same guru in Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan. And, for music critic Shanta Serbjeet Singh, after Begum Akhtar, Farida Khanum’s voice has the most character for ghazals. “It is sensuous but not earthy. It is honey-sweet but never cloying.”

It was her ‘high-speed taans and sargams; her ability to pick up a stanza of poetry, translating it to a height which saw a finesse and delicate bordering of the classical singing and swinging it rhythmically back to the sublime level of the ghazal. This was her layakari within the khayal tradition, and Khanum being the Mallika-e-Ghazal.’

Mehdi Hassan, remarked as to how she had an inherent ability of ‘mixing’—taking a passage from one raag and joining it arbitrarily with another for an easy resolution of melody- ‘a compliment, an appreciation of her knack for improvisation‘.

Few, however, gave her the tag of being an over-complicating singer, one who can’t sing a ‘straight’ tune – with remark such as, ‘Seedha nahin ga saktin,’ among Pakistani music directors of 1960s and 70s. This did ‘reach’ her ears, which she got a chance to disprove in 1976, when she sang Athar Nafees’s ghazal ‘Woh ishq jo humse rootthh gaya’ for the Pakistan Television (PTV) programme Sukhanwar.

Few others, considered Khanum, ‘an undereducated singer’, one who could not abide by the rules , due to her ‘unfinished taaleem.’ (Comparisons are drawn, inevitably, with Mehdi Hassan, the ‘natural’ Noor Jehan, and the studious but unadventurous Iqbal Bano.)

But the atmosphere, each time, Khanum performed on the stage, gradually in the subsequent decades acquired an uncritical veneration, a hallmark of musical coherence and melancholy all at the same time. Khanum’s voice, was a spectrum of too many adjectives. Steady, spellbound, mesmerizing, robust, energetic, full-throated, yet flexible.

“One can lie with words, not music,” she once said.

Apart from the signature piece under reference, some of her other gems includes, Faiz’s ‘Shaam-efiraaq ab na poochch’, Sufi Tabassum’s ‘Woh mujhse huway humkalam’ and Shakeel Badayuni’s ‘Mere humnafas, mere humnawa’, the latter incidentally also sung by Akhtar.

VI

In recent years, Khanum has lamented the lack of ghazal singers and songs released in the mainstream. During a performance at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in 2018, she explained, “I feel like there is not much to a song these days, you can’t feel the sur (tone), shayer ka dard (the poet’s pain) in the song delivery.”

She attributes this to many reasons, firstly the lack of skilled musical teachers who could train the next generation of ghazal singers, secondly the lack of commitment to the discipline of classical singing, and thirdly a lack of understanding the various dimensions of Urdu language that is used in the ghazal. For her, the solution is to bring together like-minded people who appreciate classical singing.

When asked about the falling standard and charm of ghazals, she is reported to have said,

“Well, ghazals popularly chosen are also of a lighter mode nowadays, the geetnuma ghazals. But then listeners too prefer lighter stuff. So ghazal exponents have compromised to the extent that at least the audiences remains interested. There is indeed gayaki (musicality), even if it is in a lighter mode. Look at Jagjitji (Jagjit Singh). When he sings, there is poetry, musical quality, and simplicity too, so ordinary folks can understand. That’s a good approach. He didn’t go towards, say, pop. Similarly, Ghulam Aliji has brought his own style into the ghazal and it is much appreciated. So ghazal singers have managed to make their mark, even without concentrating exclusively on sher-o-shayari (poetry).”

She is a proponent of cultural events and gatherings, where people could come together to keep the craft alive. She adds, – “We have failed to encourage ghazal and classical singing because these require rigorous training and anybody can’t take them up like pop music. Besides, there is a dire need for proper training institutes headed by music veterans, like the Sarod Ghar in India, so that the art can be promoted and passed on.”

And, “Unless I find the right kind of audience, I am reluctant to perform.”

Known for her varied emotive rendition and the miraculous swaying of hearts through the magnetic quality of her voice, but for the Partition, Khanum certainly was to be known as a classical singer in the lines of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali.

As destiny would have it, the next five decades when she branched into being a ghazal and thumri exponent, saw her become an iconic singer who was equally popular on both sides of the border. Khanum, for her admirers, remains and retains, “that all-too-familiar coil and quiver of the lips, the relentless twinkle in the eyes, the poise and aplomb that can still send many-a-hearts reeling”.

Sethi poignantly, summed up on her renditions, when he writes, ”I marvelled at her composure—and, yes, at the soundness of her training—when I saw how she conducted the audience, the accompanying musicians and the sound technicians behind the curtain with just her hand-movements and facial expressions.

And I saw—a novice observing a master, a mortal observing a living legend—how she managed her voice: the expansions in the middle octave, the careful narrowing at the higher notes, the strategic truncation of words and notes when she was running out of breath.”. This resonates with a multitude of her admirers alike.

Some of the other noteworthy tribute to the singing of this iltija, includes,

And, the very recent, re-creation in Dharma Production’s Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, 2016, by the team of Pritam, Shilpa Rao and Amitabh Bhattacharya.

In 2019, for a series on Star Plus, Naamkarann, produced by Mahesh Bhatt, sang Arijit Singh.

While these to, an extent, carried forward the enriching legacy of the iltija, we cannot resist to go back and listen to the Khanum’s version, over and over again. For, as rightly, said, ”Sometimes a creation becomes bigger than its creator“, or may be vice-versa, too in this case.

In the end,

Leave a comment